Greetings lovers of delicious tobacco. Today we will talk about tobacco.

I started writing a series of small articles on tobacco. I will try to talk in the shortest possible way about tobacco, blends and cuts.

In this article we will touch on the topic of types of tobacco. Although I smoke a pipe, I was not particularly interested in tobaccos, some of them I didn't even deal with. I Someone like me learns something new, someone will be inspired to try a new type of tobacco, for someone it will not bring anything new.

If you have comments, want to share your experience, or there is something to add, I'm waiting for your comments. Pack your pipe, we begin.

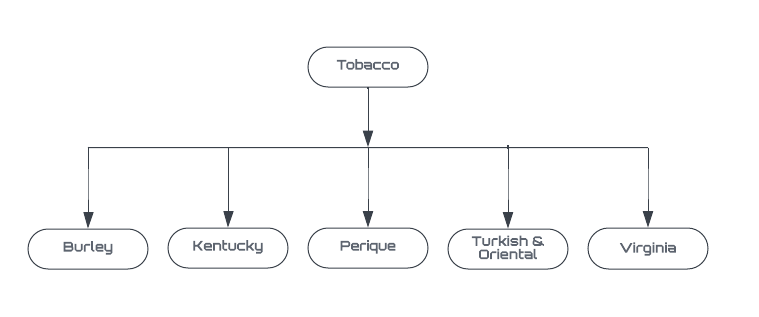

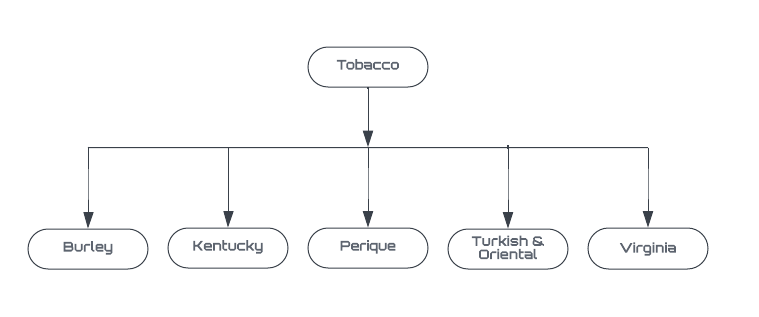

Tobacco

There is a huge variety of tobaccos used to make blends. In this post, I will try to talk about most of the tobaccos used. The pictures below show the main types of tobacco.

Before starting a story about tobacco, let's stop at Cavendish and Latakia on which sites you can find that they are classified as a type of tobacco, but this is not correct.

Cavendish is a method of drying and cutting tobacco, not a type of tobacco. It can be made using any tobacco, but the most commonly used is Virginia, Burley, Kentucky, or a mixture of both. In the process, the tobacco is subjected to pressure and heat to draw out the natural sugars from the tobacco itself. Tobacco can also be flavored or sweetened by dipping or sprinkling flavoring. Generally, what has extra sweetness is called sweetened Cavendish, and what is processed only by pressure and heat will be unsweetened Cavendish. The tobacco is then pressed, intense pressure allows the aroma to penetrate deeper, and the longer the tobacco is pressed, the more pronounced the flavor will be in the final product. You may also come across Black Cavendish – this is any tobacco subjected to heat, steam and pressure to a degree of significant darkening.Sometimes you may come across Black Cavendish, described as fire-cured tobacco. While not necessarily false, it can be confusing since most of us probably associate fireworking with a completely different process – fumigation Kentucky or Latakia.

Cavendish originated in the late 16th century when Sir Thomas Cavendish commanded a ship on Sir Richard Grenville's expedition to Virginia in 1585 and discovered that by dipping tobacco leaves in sugar (or, according to other sources, rum) from his personal supply, after whereupon he rolled up the leaves and tied them tightly with twine and canvas. After a few weeks at sea, the tobacco was cut into slices and smoked, and to the surprise of his fellow sailors, the improved taste considerably, the smoke being softer, sweeter, and more pleasant.

To recap the Cavendish above, it's not a type of tobacco, but a process that can understandably create some confusion, but it's an important distinction to make.

Latakia – Like Cavendish, Latakia isn't really tobacco either, but the process of sun-drying and fuming tobacco. Such processing of tobacco gives it a completely unique personality – it gets the aroma of fire and leather. Latakia was potentially discovered by accident when a bumper crop led to a surplus of tobacco; farmers stored surplus tobacco on the rafters of their house, which was an effective way to preserve at the time, since the smoke from open wood used for heating and lighting. This mild-temperature smoking process is one of the defining factors behind its complex flavor.

When latakia burns, it has a characteristic woodsmoke aroma accompanied by floral sweet undertones. Its origin comes from Syria, and it is named after its port city of Latakia, at this time the production in Syria was stopped due to socio-political problems and moved to Cyprus. Cyprian Latakia differs from Syrian Latakia in several key ways: the sun-drying process, the type of material used for fumigation, details during and after fumigation, and the intention of the manufacturer to undergo fermentation. Fermentation in Cypriot Latakia is not a prerequisite for The aroma profile of Cyprian Latakia is more assertive than that of Syrian Latakia, with sweeter notes of leather and smoke. The use of cedar and mastic enhances the floral tones.

Burley

Burley is a light air-cured tobacco used primarily for cigarette production. In the United States, it is produced in an eight-state belt, approximately 70% of which is produced in Kentucky. Tennessee produces approximately 20%, with smaller quantities produced in Indiana, North Carolina, Missouri, Ohio, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Tobacco Burley is produced in many other countries, mainly in Brazil, Malawi and Argentina.

The origin of White Burley tobacco is attributed to Mr. George Webb in 1864, who grew it near Higginsport, Ohio.

Burley contains almost no natural sugars, so you get a drier smoke and flavor, and unlike Virginia, Burley doesn't tend to burn too much. It is used in many Aromatic pipe blends because it easily absorbs added flavors. The color can be light to dark brown, and the taste is often described as nutty or with slight hints of chocolate.

Virginia

Virginia (VA) is a popular type of tobacco that is also used to make cigarettes, like Burley. Virginia is often used as a base tobacco in blends, but is also smoked “straight”.

Virginia – Unlike Burley, it stands out with a large amount of sugar and low oil content. The high sugar content means that Virginia ages very well when fermented in a closed container.

Natural Virginia varieties undergo changes in flavor as they age, much like fine wines. Lighter in body than oriental blends, they have a subtle complexity that makes them a favorite of many seasoned smokers.

Virginia tend to bite the tongue more than any other tobacco, so there are a number of reasons to practice proper technique with these blends.

Unlike most tobaccos, VA improves towards the bottom of the bowl. Slow smoking will ignite the underlying layers of the tobacco, deepening the flavor and reducing the chance of biting the tongue.

There are several subtypes of Virginia:

– red

– lemon

– stoved

– aged

– bright or black

All subtypes – result from different kinds of processing, but they all began simply as flue-cured leaf.

The modern chimney shed, referred to as the “mound shed”, doesn't really look like a shed at all. It looks more like a big trailer-camper without windows. In the picture below you can see what it looks like.

The modern flue-curing barn, called a “bulk barn,” does not actually look like a barn at all. It more closely resembles a big camper trailer without windows. The bulk barn is packed to capacity with ripe leaf, fresh from the field. The temperature is started at the low end of the operational range, around 100 degrees Fahrenheit, to avoid scalding the moist leaf and compromising flavor. As the leaf dries, the temperature is raised day by day to a finishing point near 165 degrees Fahrenheit after about 10 days. The air is circulated and exchanged to help push the moisture out of the leaf. Rapid drying is essential to the creation of flue-cured Virginias because it quickly shuts down the leaf’s metabolic processes. The natural sugars are “locked in” before they can break down. It follows that only flue-curing can produce a true, naturally sugary Virginia pipe tobacco. (In today’s commercial markets, there is no air-dried Virginia, just as there is no flue-cured burley.) By the end of the curing process, the leaf is gold- or lemon-colored, and it is so dry and brittle it cannot be handled without shattering. Water misters are then used to reintroduce moisture to the leaf (about 14 percent by weight) to make the tobacco pliable again. It can then be removed from the bulk barn and baled for transport and further processing.

The color ranges from bright hay-yellow to deep red to almost black, and each shade has a different flavor profile due to its sugar content. Tobacco that dries longer (and therefore darker in color) will be less sweet than tobacco that has been dried quickly. The brighter varieties are lighter and “fresher” with hints of something like hay, citrus and summer days, while the darker ones tend to have a deeper, fuller flavor. darker taste with hints of dried fruit, caramel and chocolate.

The taste of Virginia is sweet and light, but it burns quickly.

The modern flue-curing barn, called a “bulk barn,” does not actually look like a barn at all. It more closely resembles a big camper trailer without windows. The bulk barn is packed to capacity with ripe leaf, fresh from the field. The temperature is started at the low end of the operational range, around 100 degrees Fahrenheit, to avoid scalding the moist leaf and compromising flavor. As the leaf dries, the temperature is raised day by day to a finishing point near 165 degrees Fahrenheit after about 10 days. The air is circulated and exchanged to help push the moisture out of the leaf. Rapid drying is essential to the creation of flue-cured Virginias because it quickly shuts down the leaf’s metabolic processes. The natural sugars are “locked in” before they can break down. It follows that only flue-curing can produce a true, naturally sugary Virginia pipe tobacco. (In today’s commercial markets, there is no air-dried Virginia, just as there is no flue-cured burley.) By the end of the curing process, the leaf is gold- or lemon-colored, and it is so dry and brittle it cannot be handled without shattering. Water misters are then used to reintroduce moisture to the leaf (about 14 percent by weight) to make the tobacco pliable again. It can then be removed from the bulk barn and baled for transport and further processing.

The color ranges from bright hay-yellow to deep red to almost black, and each shade has a different flavor profile due to its sugar content. Tobacco that dries longer (and therefore darker in color) will be less sweet than tobacco that has been dried quickly. The brighter varieties are lighter and “fresher” with hints of something like hay, citrus and summer days, while the darker ones tend to have a deeper, fuller flavor. darker taste with hints of dried fruit, caramel and chocolate.

The taste of Virginia is sweet and light, but it burns quickly.

Perique

Perique – Is the “truffle” in the world of tobacco, got this nickname not only because it is as rare as a truffle, but also for its flavor and aroma characteristics. . When the Acadians made their way into this region in 1776, the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes were cultivating a variety of tobacco with a distinctive flavor. A farmer named Pierre Chenet is credited with first turning this local tobacco into what is now known as Perique in 1824 through the labor-intensive technique of pressure-fermentation. It is reported by authorities on tobacco that Perique is based on a variety of Red Burley leaf. The Tobacco Institute says perique has been shipped out of New Orleans for more than 250 years and is considered to be one of America's first export crops.Perique is produced exclusively in St. James Parish, Louisiana. The production process begins with air drying, but then undergoes additional unique processing within 12-18 months. The cured leaf is packed in large oak whiskey barrels and placed under pressure where it undergoes anaerobic fermentation. Periodically during fermentation (at least three times), the tobacco is unpacked, the leaves are stripped, aired, and then repackaged for additional months of pressure treatment. This process significantly alters and enhances the taste of the leaf. Perique has an intense aroma and is rarely smoked on its own. It's a spice leaf, usually added in small doses (typically a few percent by weight in blends that use Perique), and it adds a savory note – fig pepper with hints of fermented plum, olive and pine.

Perique – Is the “truffle” in the world of tobacco, got this nickname not only because it is as rare as a truffle, but also for its flavor and aroma characteristics. . When the Acadians made their way into this region in 1776, the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes were cultivating a variety of tobacco with a distinctive flavor. A farmer named Pierre Chenet is credited with first turning this local tobacco into what is now known as Perique in 1824 through the labor-intensive technique of pressure-fermentation. It is reported by authorities on tobacco that Perique is based on a variety of Red Burley leaf. The Tobacco Institute says perique has been shipped out of New Orleans for more than 250 years and is considered to be one of America's first export crops.Perique is produced exclusively in St. James Parish, Louisiana. The production process begins with air drying, but then undergoes additional unique processing within 12-18 months. The cured leaf is packed in large oak whiskey barrels and placed under pressure where it undergoes anaerobic fermentation. Periodically during fermentation (at least three times), the tobacco is unpacked, the leaves are stripped, aired, and then repackaged for additional months of pressure treatment. This process significantly alters and enhances the taste of the leaf. Perique has an intense aroma and is rarely smoked on its own. It's a spice leaf, usually added in small doses (typically a few percent by weight in blends that use Perique), and it adds a savory note – fig pepper with hints of fermented plum, olive and pine.

Kentucky

Kentucky – A type of Burley that is fire dried rather than air dried like Latakia.

But Kentucky doesn't taste as heavy or smoky, but is actually quite flavorful and playful. Not as strong as Perique in terms of nicotine, but it's higher and so it's mostly used in small amounts in blends where it adds a bit of tasty appeal.

Turkish & Oriental

Virginia and Burley tobaccos have completely different sugar and oil content. Meanwhile Oriental tobacco is known for its balanced composition. Oriental tobacco varieties, harvested from small-leaved plants, are often dried and dried in direct sunlight. Turkish tobacco plants usually have more and smaller leaves.

As the name suggests, oriental tobacco comes from the Mediterranean region between Greece, Turkey and Bulgaria. In fact, Oriental tobacco is often used to refer to many different varieties of tobacco.

– Greek Oriental Tobacco

– Basma: Pressed tobacco from Western Greece.

– Djebel: Mild, pressed tobacco from Thrace in Northeastern Greece.

– Drama: Sweet and subtle Greek tobacco.

– Kavala: Large and dark aromatic Greek tobacco.

– Katerini: Greek variety of Samsun with a mild flavor.

– Mahala: An alternative pressed Basma tobacco from Kavala.

– Trebizond: A Greek variety of Basha Bagli tobacco.

– Xanthi: Strong pressed Greek tobacco from Thrace similar to Basma.

– Yenidje: Famous strong tobacco from Greece with a reddish colour.

– Turkish Oriental Tobacco

– Basha Bagli: Strong and sweet Turkish tobacco with high nicotine.

– Baffra: More rustic alternative to Samsun-Maden.

– Bursa: Heavy and uncharacteristically large Turkish tobacco.

– Izmir: Mild but flavorful Aegean Turkish tobacco.

– Samsun-Maden: Mild yet flavorful Turkish variety from the Black Sea.

– Smyrna: Alternative name for Izmir tobacco.

- Other Oriental Tobacco

These are a few well-known Oriental tobacco varieties that aren't native to either Greece or Turkey:

- Dubek: Sweet and aromatic Macedonian tobacco.

- Persian Shiraz: Rare Iranian tobacco.

- Shek-el-Bint: Syrian tobacco traditionally used for Latakia curing.

What’s the Difference Between Oriental & Turkish Tobacco?

Interestingly, tobacco was introduced to the Ottomon Empire by the Spanish from the Americas. As such, none of the above varieties are truly native to their countries.

Similarly, the monikers “Turkish” and Oriental” are often used interchangeably due to their shared Ottoman heritage. Today, many of the varieties that were predominantly “native” to one country may be grown throughout the region today.

Furthermore, the specific tobaccos listed above are hard to find separately but are usually blended together by manufacturers.

Given the many different strains that are referred to as Turkish and Oriental tobacco, they can greatly vary in flavour. Turkish and Oriental tobacco may be earthy and spicy or even floral and herbaceous.

Turkish and Oriental tobacco is often added to blends alongside Latakia to provide a bold smoking experience. However, they may also be used in combination with Virginia and Perique tobacco too.

Notes

Such resources helped in writing the material:

https://www.tobaccopipes.com/

https://www.smokingpipes.com/

https://pipedia.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

https://burleytobaccoextension.ca.uky.edu/varieties

https://www.leafonly.com/chewing-tobacco-leaf/tobacco-seeds/tobacco-seeds-perique

Packing: Easy

Aging: Medium

Packing: Easy

Aging: Medium Packing: Easy

Aging: Low

Packing: Easy

Aging: Low Packing: Moderate

Aging: Medium

Packing: Moderate

Aging: Medium Plug – is a bar of pressed tobacco, which consists of a layer of different types of tobacco, which are subsequently heated and pressed. Since it is a pressed tobacco, the air exchange in it is minimal, which allows it to have a very good aging potential.

Packing: Difficult

Aging: High

Plug – is a bar of pressed tobacco, which consists of a layer of different types of tobacco, which are subsequently heated and pressed. Since it is a pressed tobacco, the air exchange in it is minimal, which allows it to have a very good aging potential.

Packing: Difficult

Aging: High Packing: Moderate

Aging: High

Packing: Moderate

Aging: High Packing: Difficult

Aging: High

Packing: Difficult

Aging: High Packing Difficulty:

Aging Potential:

Packing Difficulty:

Aging Potential:

The modern flue-curing barn, called a “bulk barn,” does not actually look like a barn at all. It more closely resembles a big camper trailer without windows. The bulk barn is packed to capacity with ripe leaf, fresh from the field. The temperature is started at the low end of the operational range, around 100 degrees Fahrenheit, to avoid scalding the moist leaf and compromising flavor. As the leaf dries, the temperature is raised day by day to a finishing point near 165 degrees Fahrenheit after about 10 days. The air is circulated and exchanged to help push the moisture out of the leaf. Rapid drying is essential to the creation of flue-cured Virginias because it quickly shuts down the leaf’s metabolic processes. The natural sugars are “locked in” before they can break down. It follows that only flue-curing can produce a true, naturally sugary Virginia pipe tobacco. (In today’s commercial markets, there is no air-dried Virginia, just as there is no flue-cured burley.) By the end of the curing process, the leaf is gold- or lemon-colored, and it is so dry and brittle it cannot be handled without shattering. Water misters are then used to reintroduce moisture to the leaf (about 14 percent by weight) to make the tobacco pliable again. It can then be removed from the bulk barn and baled for transport and further processing.

The color ranges from bright hay-yellow to deep red to almost black, and each shade has a different flavor profile due to its sugar content. Tobacco that dries longer (and therefore darker in color) will be less sweet than tobacco that has been dried quickly. The brighter varieties are lighter and “fresher” with hints of something like hay, citrus and summer days, while the darker ones tend to have a deeper, fuller flavor. darker taste with hints of dried fruit, caramel and chocolate.

The taste of Virginia is sweet and light, but it burns quickly.

The modern flue-curing barn, called a “bulk barn,” does not actually look like a barn at all. It more closely resembles a big camper trailer without windows. The bulk barn is packed to capacity with ripe leaf, fresh from the field. The temperature is started at the low end of the operational range, around 100 degrees Fahrenheit, to avoid scalding the moist leaf and compromising flavor. As the leaf dries, the temperature is raised day by day to a finishing point near 165 degrees Fahrenheit after about 10 days. The air is circulated and exchanged to help push the moisture out of the leaf. Rapid drying is essential to the creation of flue-cured Virginias because it quickly shuts down the leaf’s metabolic processes. The natural sugars are “locked in” before they can break down. It follows that only flue-curing can produce a true, naturally sugary Virginia pipe tobacco. (In today’s commercial markets, there is no air-dried Virginia, just as there is no flue-cured burley.) By the end of the curing process, the leaf is gold- or lemon-colored, and it is so dry and brittle it cannot be handled without shattering. Water misters are then used to reintroduce moisture to the leaf (about 14 percent by weight) to make the tobacco pliable again. It can then be removed from the bulk barn and baled for transport and further processing.

The color ranges from bright hay-yellow to deep red to almost black, and each shade has a different flavor profile due to its sugar content. Tobacco that dries longer (and therefore darker in color) will be less sweet than tobacco that has been dried quickly. The brighter varieties are lighter and “fresher” with hints of something like hay, citrus and summer days, while the darker ones tend to have a deeper, fuller flavor. darker taste with hints of dried fruit, caramel and chocolate.

The taste of Virginia is sweet and light, but it burns quickly.