TEN-T and military logistics and availability using the example of the ScanMed corridor and its current sub-projects

Preliminary remarks from the authors

We are at the beginning of a new age of wars. Wars between transnational power blocs, wars between existing and emerging nation states and wars against fleeing and rebellious populations. Wars over strategic resources, wars over food and water, wars over geostrategic power constellations and territorial claims. But no matter what the wars of the present and future may be about, we firmly refuse to join any party in them, as every war is directed exclusively against the exploited and oppressed of this world and only benefits the powerful to increase their wealth and their dominion over life. However, it cannot follow from this that we will passively watch as the rulers prepare the slaughter, commit genocides and massacres and bring destruction and misery upon people and life itself. While it is clear that we will never turn our guns on each other at the command of the LORDS, nothing in the world will prevent us from fighting with our own weapons against the sheer facilitation of war, against nationalist propaganda, the military-industrial process of progressive genocide, and not least the sheer infrastructure of war. And it is precisely this infrastructure of war, or today's modern “dual use” infrastructure of the “peaceful” exploitation of people and nature as well as the military destruction of the two, that we want to focus on in this article using the example of the so-called ScanMed corridor (Scandinavian-Mediterranean corridor) as one of the EU's most important infrastructure transport axes and some of its current sub-projects for expansion and upgrading. In doing so, we do not want to show once again that the fight against war always includes the fight against “peaceful”, i.e. frictionless, exploitation and destruction, i.e. against the industrial and colonial project, but rather to make a small contribution to pointing out concrete points of attack in this fight and at the same time to encourage people to carry out their own analyses of the military-industrial complex, its raw materials and its logistics, with nothing less in mind than its efficient sabotage. For we miss such an analysis all the more painfully because we are of the opinion that our ability to fight domination (and its wars) is irrevocably dependent on knowing its infrastructures, understanding its functional mechanisms and, last but not least, having the necessary skills and a certain routine in attacking it at identified weak points.

The Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T)

The trans-European transport network (TEN-T or TEN-V for transeuropäische Verkehrsnet) is a network of road, rail, air and waterways planned by the EU to ensure the fast and smooth transportation of goods, raw materials, in some cases also energy (carriers) and finally, often unmentioned, but in the strategy papers, military equipment, supplies and troops across national borders. It consists of a core network, which in turn is spanned by nine so-called multimodal core network corridors across the entire territory of the EU. These corridors connect, for example, the North Sea region with the Mediterranean region, the Baltic Sea with the Adriatic, the Mediterranean cities in a west-east direction, along the Rhine and Danube or the Atlantic coast. They are multimodal, which means that they consist at least of road and rail routes, often also – or at least partially – of waterways, that they connect airports and deep-sea ports by land, i.e. if one mode of transportation fails or is delayed, it should be easy and uncomplicated to replace it with a parallel transport route along the same transport axis. It is no coincidence that this redundancy of transport routes, this multimodality, is a requirement for military transport axes used for the movement of troops and their equipment and supplies, as is the suitability for axle loads over 22.5 tons on around 94% of the route; after all, this military usability was taken into account by the EU and its member states from the outset.

The ScanMed corridor

The ScanMed corridor, i.e. the transport corridor connecting the Scandinavian countries with the Mediterranean, is the longest core network corridor in the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) and runs from Oslo and Helsinki via Rostock – Berlin – Leipzig / Hamburg – Bremen – Hanover, Nuremberg – Munich – Innsbruck (Brenner) – Verona – Bologna – Florence – Rome – Naples – Palermo to Malta. It crosses the North Sea – Baltic Sea core network corridor in Bremen, Hanover, Berlin and Hamburg, the Mediterranean core network corridor in Verona and the Rhine – Danube corridor in Munich and Regensburg. It also connects the seaports of Hamburg, Gothenburg, Bremen, Rostock and the airports of Munich, Berlin, Leipzig and Hamburg to the transport routes on land. Around 1100 freight trains leave the port of Hamburg every week for inland destinations along the ScanMed corridor. Conversely, this corridor connects most of the larger and medium-sized Mediterranean ports in Italy with Germany via the Brenner Pass. Here, it allows time savings of several days when transporting goods from or to the so-called Far East, if they can be handled by land instead of taking the sea route via the port of Hamburg. What applies to “civilian” goods also applies to military goods and troops thanks to the “dual-use” strategy in the area of infrastructure. The ScanMed corridor not only connects the North Sea naval bases of the German Armed Forces with the Mediterranean ports of Italy, but also makes it possible to balance troop and material movements via some of the west-east axes. For example, we still remember well how US military equipment that landed in ports such as Palermo or Bremerhaven as part of the NATO exercise “Defender 2020” took precisely these routes to the respective US bases, especially in Germany, from where it would have left for Poland if the exercise had not been canceled. From a military point of view, the ScanMed corridor is also hardly dispensable with regard to the German arms industry and its supply of raw materials and semi-finished products, both in “peacetime” and in the event of war. The arms industry based in the Munich/Ingolstadt/Augsburg metropolitan region in particular, as well as the Bavarian chemical triangle near Burghausen/Burgkirchen/Trostberg/Waldkraiburg, handle their logistics along this corridor which is relevant for the arms and oil supply of southern Germany, mainly and “out of necessity” (as there is largely no alternative).

Current bottlenecks and corresponding expansion projects

The two most significant bottlenecks in the ScanMed corridor are currently at the Brenner Pass and the Fehmarn Belt, and they particularly affect rail traffic. At the so-called Fehmarn Belt, motor vehicles and trains travel on the so-called “Vogelfluglinie”, the most direct connection between the metropolises of Copenhagen and Hamburg, an approximately 19-kilometer route between the German island of Fehmarn and the Danish island of Lolland, so far by ferry. The Fehmarn Belt Tunnel, which is to be built as a road and rail tunnel with 4 tubes for traffic, as well as a rescue and maintenance tube by 2029, is intended to upgrade this section of the route in the future and thus eliminate the bottleneck caused by the ferry service. At the same time, the Fehmarnsund Bridge, which connects the German mainland and Fehmarn, is to be replaced by another sea tunnel, the Fehmarnsund Tunnel, which is to be built at the same time to accommodate the growing volume of traffic and in particular the 835-metre-long freight trains that will then run there.

The second major bottleneck of the ScanMed corridor is in the Alps, more precisely at the Brenner Pass. On one of the most important Alpine crossing routes in Europe, rail transport in particular, especially rail freight transport, poses such a major challenge due to the steep gradients of the route that it is often more economical to transport goods by truck. The Brenner Base Tunnel, which is due to be completed by 2032, aims to change this. In order to guarantee a stable connection, new access routes are also being built or expanded both in the north (Austria and Germany) and in the south (Italy) to allow capacities of several hundred trains per day.

In addition, there are numerous smaller bottlenecks and expansion stages on sections of the ScanMed corridor that do not comply with the EU's requirements for the core network corridors. In rail transport, for example, the northern access route of the Brenner Base Tunnel, which is to be newly built between Grafing and Rosenheim, as well as the planned bypass routes between Hanover and Hamburg to be built as part of the Optimized Alpha E + Bremen, and the upgrading of existing routes in Germany are still missing. The railroad line between Hof and Regensburg, which is part of the so-called Eastern Railway Corridor, has not yet been electrified. A new Munich-Ingolstadt line with a connection to Munich Airport is also included in the specifications for the ScanMed corridor to be completed by 2030. Numerous freight handling stations also do not currently meet the required standards, particularly with regard to a freight train length of more than 740 meters, including Munich, Nuremberg, Hanover, Rostock, Lübeck, Großbeeren, Schkopau and Hamburg-Billwerder.

Requirements for military usability of the corridor

To ensure that the transport axes, which are primarily built for civilian purposes, can actually be used for military purposes as part of a “dual use” strategy, a number of requirements must be met, such as those defined in the European “Action Plan on military mobility”. These include, for example, permissible axle loads of 22.5 tons, as well as the multimodality of the corridors, i.e. the ability to switch more or less at any time from road to rail or waterway and vice versa, should one of the parallel infrastructures be seriously damaged. In addition to parallel transport routes of various types, these are primarily transhipment stations and ports that can transfer goods from road to rail and vice versa, or from ship to road/rail. Such transhipment stations, known as Rail-Road Terminals as part of the EU infrastructure project, are located along the ScanMed corridor in a south-north direction within Germany in Munich, Nuremberg, Hanover, Berlin, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Hamburg, Lübeck and Rostock.

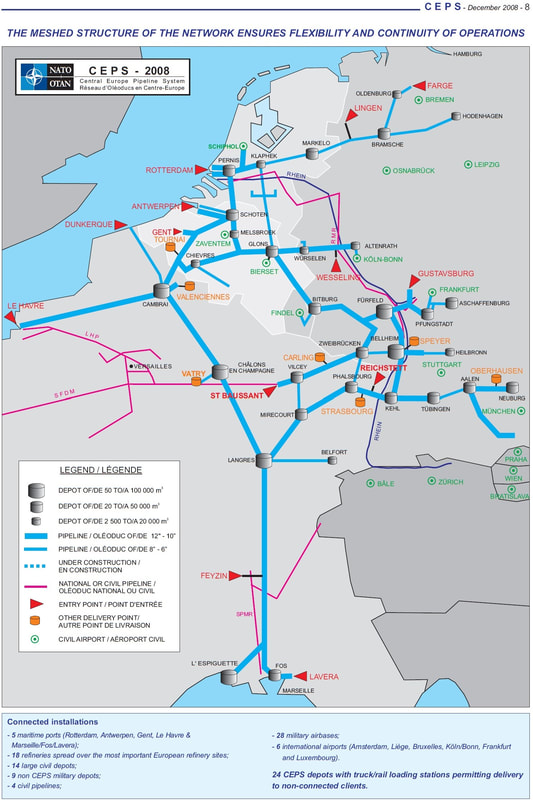

In addition, a sufficient supply of fuel along the transport corridors is essential for their military usability. This is because the transportation of troops and military equipment consumes a gigantic amount of energy, which cannot simply be conjured up. Countless fuel stations for cars, trucks, trains, planes and ships are needed to supply the civilian transportation system, which is supplied with the necessary fuel on a daily basis using sophisticated logistics consisting of pipelines, freight trains and tankers. Roughly speaking, the fuel produced in the refineries (where the crude oil required for this usually arrives via pipeline, see below) is transported via pipelines, tank ships and tankers to so-called tank farms, from where it is also transported by tanker or truck to the various filling stations, as well as to smaller and more distant tank farms. Some strategically important tank farms for the military in Germany and throughout Europe are connected by a NATO pipeline network, which is now sometimes also operated by civilian operators, but ensures military priority use if necessary. There are a total of 12 active fuel refinery sites in Germany, located in Burghausen, Brunsbüttel, Gelsenkirchen, Hamburg-Haburg, Hemmingstedt (Heide), Ingolstadt, Karlsruhe, Cologne, Leuna, Lingen (Ems), Schwedt (Oder) and Neustadt an der Donau / Vohburg an der Donau. They are supplied via four central pipeline systems: the North-West oil pipeline, which together with the North German oil pipeline supplies the refineries in Lingen, Cologne, Gelsenkirchen and Hamburg-Harburg with crude oil via the Wilhelmshaven oil port, the South European pipeline, which supplies the refinery in Karlsruhe from the port of Marsaill and is also connected to the Transalpine oil pipeline (TAL), which in turn pumps oil from the port of Trieste to Burghausen, Ingolstadt, Karlsruhe and Neustadt/Vohburg on the Danube, as well as a pipeline from Rostock to Schwedt and from there to Lingen, which has reached its capacity limits, particularly since the boycott of Russian oil, which previously also arrived in Schwedt via the Freundschaft oil pipeline, and is to be developed and expanded at a cost of 400 million euros. From the refineries, the fuel takes a mostly opaque and logistically constantly rescheduled route via pipelines, tankers and trucks to the corresponding tank farms or directly to the various filling stations.

However, NATO's Central European Pipeline System (CEPS), which has military sites in Lauchheim-Röttingen (Aalen), Altenrath, Mainhausen (Aschaffenburg), Bellheim, Niederstedem (Bitburg), Boxberg, Bramsche, Wonsheim (Fürfeld), Hademstorf (Hodenhagen), Hohn-Bollbrüg, Untergrupppenbach-Obergruppenbach (Heilbronn), Huttenheim, Kork (Kehl), Weichering (Neuburg an der Donau), Littel (Oldenburg), Pfungstadt, Bodelshausen, Würselen and Walshausen (Zweibrücken), as well as civilian facilities in Ginsheim-Gustavsburg, Honau, Krailing (Unterpfaffenhofen), Oberhausen (Neuburg an der Donau) and Speyer, totals 24 fuel depots in Germany alone with an estimated fuel capacity of between 20,000 and 100,000 cubic meters per depot. The refineries in Wesseling (Cologne), Lingen (Emsland) and the Gustavsburg tank farm, which is strategically located at a railroad junction and on the Rhine and even has its own port, serve as feed-in points for fuel supplies within Germany. In addition, numerous other fuel depots connected to the CEPS have rail links and can therefore be converted into feed-in points. Finally, there are the North Sea and Mediterranean ports, as well as the numerous fuel depots in Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France, and the refineries connected to them, to compensate for any fuel shortages. However, this is also desperately needed, as the fuel requirements of an army on the move are almost immeasurable. A tank, for example, consumes at least around 150 liters of diesel per hour of operation (large battle tanks can also consume a good 600 liters!), while a fighter jet can quickly consume between 5,000 and 10,000 liters of kerosene per hour of operation. Of course, you can count the days on one hand until the fuel reserves in the military fuel depots are used up. For the ScanMed axis in particular, it is of course noticeable that the route between the Munich-Ingolstadt metropolitan area and Bremen/Hanover is relatively far removed from the CEPS military pipeline network, which is essential for Germany, and that either corresponding feeder corridors must be used on this route, which run via road and rail, or that in this area there would also have to be increased military recourse to civilian fuel supplies. Incidentally, the company operating the CEPS on German soil is Fernleitungs-Betriebsgesellschaft (FBG), while the tank wagons required for rail transportation were once handed over to VTG. Some of the tank farms are also currently managed by TanQuid.

In the future, the new hydrogen pipelines to be built and the infrastructures that are being created around the emerging energy source, which are being pushed with great vigor by the Green War Party in particular, will become increasingly important for supplying the military with fuel. These will presumably initially supply the refineries that continue to supply fuels, but in the longer term, fuel conversions to hydrogen-powered engines are certainly to be expected. At the very least, the planned hydrogen core grid envisages opening up all regions along the ScanMed corridor.