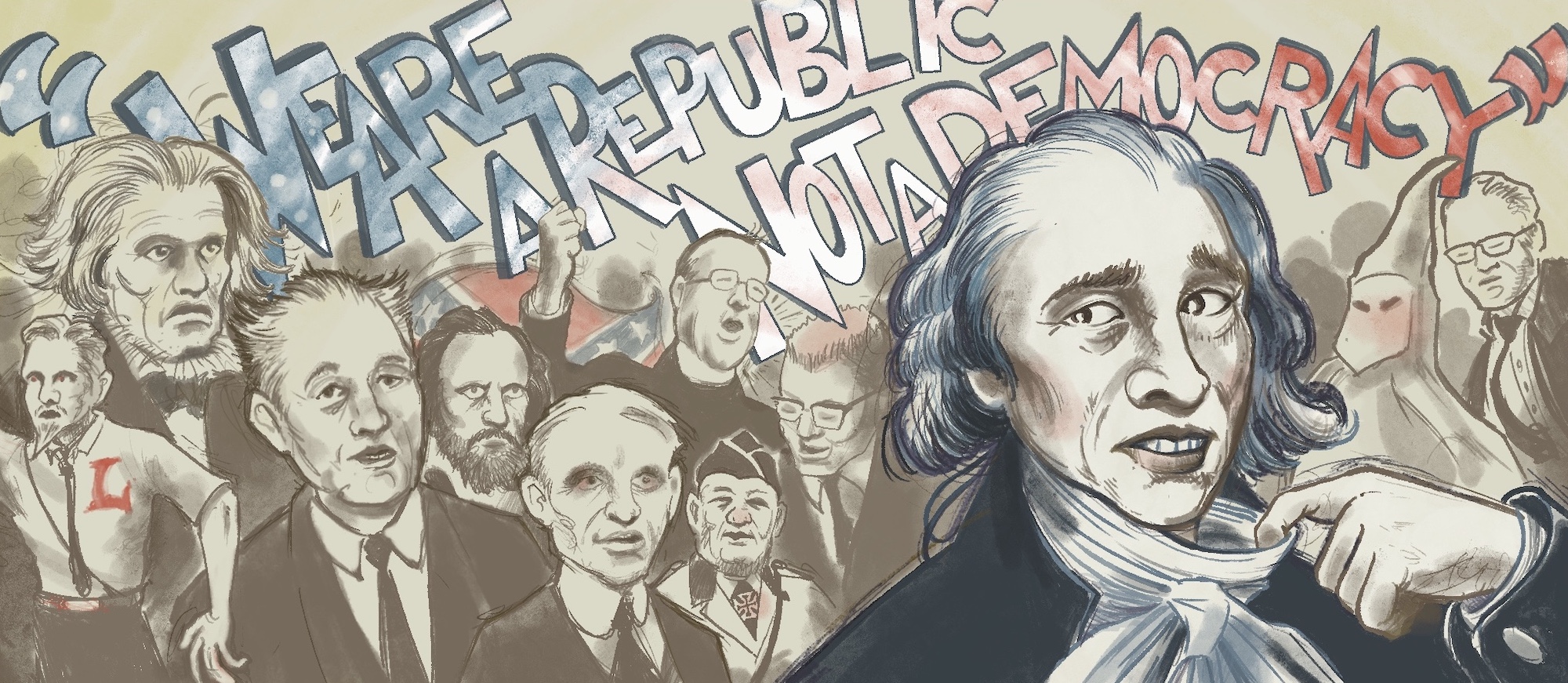

A Brief but Bigoted History of “We're a Republic, Not a Democracy” (1 of 4: barely concealed American racism & xenophobia)

Tracing a conservative slogan's chronological arc from an inconspicuous tagline to a regurgitated maxim of secessionists, segregationists, proto-fascists, neo-fascists, and duplicitous Right-wing political critters.

(this is an updated version of the article posted May 10, 2023. There was a technical issue, so this first part is split into two sections. Then we carry on with the remaining 3 parts. This can be read over on Medium as well.)

The American system of government is packed with old conundrums and intricacies. Those who passed their high school AmGov classes may remember learning that its founding documents are not exactly the most straight forward. The world’s oldest constitution exudes a sense of “flying by the seat of one’s pants while trying to sound fancy.” Good or bad, most modern nations have since attempted to make their charters more updatable and more verbose to smartly avoid legal confusions and misinterpretations.

From the outside, it is almost mesmerizing how every other Supreme Court decision tends to be some epic game-changer boiling down to pithy interpretations of 250-year-old vaguery and vibes. As well, an incessant American addiction to embracing ahistoric viewpoints helps little and their adoption by disingenuous political characters with poor understanding of etymology seems to make the political waters even muddier.

Frankly, the particularly untidy issue of how to classify the United States of America’s structure of government has already been beaten to death by a plethora of well-written academic literature and dissertations from fellow history-nerds. If quibbling over political theories were a pack of horses, they would have been a vat of glue well before any of our grandparents were born. To the vast majority of Americans, the nomenclature means much less than how it works or how they are represented in a land that purports to be created by “We The People” to establish justice and keep themselves generally healthy, safe, and secure.

Despite the country’s original architects being overly concerned with snazzy wording as they cobbled together a nation as technologically advanced as a contemporary Amish community, there has been a long line of smug pedants who go out of their way to whip out the ol’ “We are a Republic, Not a Democracy” trope at the end of rants over modern issues into the online ether. Almost as if it were some magical mic-drop (a very rare thing in Amish country) we have no choice but to nod and begin praisingly clapping at. Unfortunately most of these self-classifying scholars have not been using it for sincere discussions over antique terms, instead opting to whip it out as justification of divisive political policies that would be detrimental to anybody who was not an already well-off male of European descent.

Much has already been written about the authoritarianism surrounding the invocation of this 7-word canard and the insinuations when invoked by very conservative personalities. Some have nerdily discussed the phrase’s ambiguous usage by a few of America’s founders or how it harks back to America First Committee supporter's writings to later be picked up by their Bircher inheritors. But typically, the discourse tends to gloss over the volumes of antisemitism, moral panickery, classism, xenophobia, and unabashed racism accompanying its usage & the users of the expression.

So a deep spelunking into archives of governmental records, academic publications, newspapers, literature, speeches, and websites galore was undertaken. It may not look it, but we have attempted to tell the quickest story of how this “We’re a Republic Not a Democracy” cliche has been brandished since spawned by the words of “Plubius” in 1787. As we whip through the timeline and profiles, the reader will notice that there is an overwhelming amount of context. Piles of links are provided to help spell out details which would take a chapter or more in a book to break down.

To make this a bit easier for all of us to digest, we have broken this up into 4 parts. The first two follow the historic trail of the idiom’s usage. We then finish with residual but obligatory context, also in two parts, which should give most any sane American a bit of the shudders anytime they hear this cretinous expression going forth.

(in order to save the author & reader some sanity, we will often use “RNAD” when referring to this article’s catchphrase going forth as well)

Plubius

Like an Appeal to some 235-year-old Authority, “We Are A Republic And Not A Democracy” is ultimately referencing Madison’s Federalist #10 essay regarding how to sustain public interests without infringing on the rights of individuals. As “Plubius,” Madison discusses combining elements of democracy and republicanism to create a decentralized system of government to deal with a populace spread out over a capacious confederacy. Endless discussions have been had over what a handful of America’s framers really meant by such terminology and similar remarks since the pseudonymous disquisition appeared on newsprint in the closing months of 1787.

Particularly over the last century, conservatives have proudly pointed to Madison’s prose like it was some kind of final-say. As if history stopped over two centuries ago and words’ meanings never evolve or writers are simply humans who can also have different interpretations and blind-spots. Historians and pedantic nerds (like yours truly) tend to point out that “democracy” and “republic” had been used almost interchangeably long before the U.S. signed off on its constitution. Madison and others involved with constructing a novel monarch-less government had already used both terms to refer to their nation. We will come back to this on the backside, but those who penned the essays as “Plubius,” otherwise known as the Federalist Papers, acknowledged that they were using “democracy” specifically to refer to a “pure democracy” (direct democracy as we tend to call it now). Much of it in order to evade having to consider the unfathomable logistics an unfettered system of government for a bulky and inequitable society spread across a landmass, especially in the era of slavery and horse & buggies, required without shooting themselves in their own well-heeled feet.

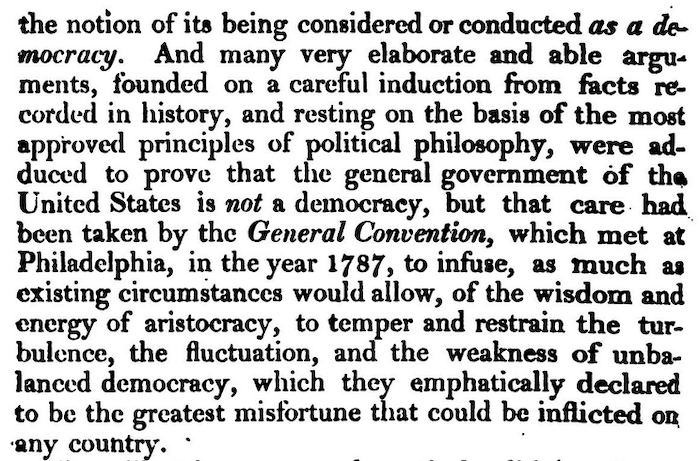

Making use of some fancy internet sleuthin’ skills (i.e., running wads of terms through a myriad of search filters) we eventually came across an 1818 book with looks to be one of the earliest passages declaring that “the United States is not a democracy” because “illustrious sages” of the Constitutional Convention had thoughtfully built in “the wisdom and energy of aristocracy” to temper the “turbulence” & “fluctuation and weakness of unbalanced democracy.” Nevertheless, as per John Bristed’s America and Her Resources, the novice nation was a “representative republic […] obliged to exist too much by exciting and following the passions and prejudices of the multitude.” The chief crux of the book was cautioning that allowing immigrants and Free Blacks to be involved in any component of the local, state, or federal political process would lead to the country’s suicide.

The 500 page tome also stressed the evils of slavery. More so for fear of slave-owners’ safety, if their slaves would ever have the gumption to revolt against their “masters.” Being opposed to slavery on the grounds of not wanting to be around Black people was not all that uncommon in abolitionist circles. Bristed did his part by proposing that the “wretched African race” be sent back to help civilize the “immense continent of Africa, containing a hundred and fifty millions of Mahomedans and Pagans, steeped in ignorance, superstition, brutality, vice, and crime.”

Bristed’s book set the uncanny tone for the rhetoric and the persuasion of people who would subsequently employ anti-democratic and RNAD verbiage to bolster unnerving political positions within specious arguments that basically amounted to the “othering” of their fellow countrymen. Revulsion to any demographic change is now a very familiar fash-y dinger and although this was less than a generation into a new America, he was by far not the first to cry about his less-than-white neighbors. (here's looking at you Benjamin Franklin) But to promote his proposed fixes for fabricated issues, such as using the gallows for minor crimes to curb a burgeoning population of non-English immigrants and Black people, Bristed had to really sell it. Like an early-19th century version of a recent tweet from some blue-checked white-replacement-obsessed account that the current CEO of Xchan regularly interacts with, the Episcopalian clergyman (and immigrant) had his rage-farming shtick down:

The sparse amount uncovered from online print and governmental records suggests that the polemical RNAD was overall atypical for the next half century. Yet discussions concerning what was and was not “democratic” about the fledgling nation and the fundamentals which made up its relatively progressive and dynamic society became en vogue. Authors and journalists visiting from Europe, like Touqueville, built careers based around this discourse. Democratic movements beyond the eastern shores of the Atlantic bloomed in fits & starts, depending on how oppressive or progressive the local authorities decided to be.

Nullification & Slavery

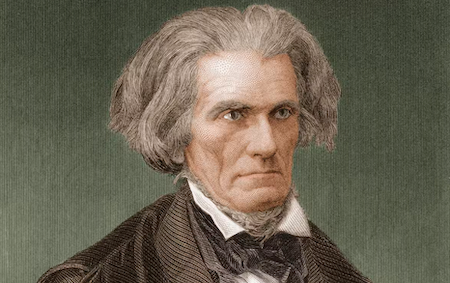

It would be irresponsible not to shine a brief spotlight on South Carolina's John C. Calhoun (DR/D-SC) and the Nullification Crisis of the early 1830s. Although quite the neckbeard-rocking nationalist in his early political career, Calhoun was an exceptionally racist (even for his time) defender of slavery who resigned from being Andrew Jackson’s vice-president to represent South Carolina’s attempt to void federal tariffs. Calhoun professed that all states are sovereign entities and the Constitution was only a compact of separate sovereign states who have the right to annul federal laws which they may deem unconstitutional. In reality, the Constitution’s Article III and Supremacy Clause, as well as several Federalist papers, including Madison’s № 39 and № 44, make it clear that states cannot just abrogate federal law and would instead need to take it up with the Supreme Court.

The banal “States’ Rights” is simply repackaged Calhoun’s “concurrent majority,” the principle underpinning his doctrine of nullification. To prevent tyranny of the “majority” (free-states not reliant on the 3/5ths clause for electoral college or Congressional representation), the “minority” (slave-states) can void federal laws like those concerning tariffs, anti-slavery, anti-segregation, voting rights, or health care access.

We should note that while Calhoun had used RNAD to describe his home-state of South Carolina a few years prior, he directly referred to the “Federal Republic” as also being a “Constitutional Democracy” designed by “the immortal framers of our Constitution” in 1841. And although peculiarly remembered as a “defender of minorities,” he was quite clear that the only minority he cared protecting was a slave-holding South, demonstrating that the opposition to federal tariffs were a precursor for a fight to maintain slavery’s legality. Small wonder that the RNAD argument harnessed to “fend off a tyranny of the majority” would become part of the conservative “States’ Rights” jargon a century later. As historian Richard Hofstadter put it…

Another anti-democracy panjandrum of the era, Orestes Brownson, was the originator of the xenophobic-laden term “Americanization” and a pioneer in the national pastime of obsessing over the downfall of the country, believing that democracy would “lower the standard of morality, to enfeeble intellect, to abase character, and retard civilization.”

Brownson argued that the biggest national threat lied in affording any autonomy to the unpropertied working class of the cities, which would somehow lead to an aristocracy of elected wealthy business owners. Interesting given that the Constitution’s Framers essentially constructed something that, although progressive for its time, would technically be considered an oligarchy built on many affluent familial ties. And seeing as how less than a century later wealthy industrialists would make an inverted argument against democracy, in a Mencken-esque way, he was not wholly incorrect. Of course it would be expected that a government built as a republic (a political parallel to a company ran by a board of directors) would not also turn into “a government run like a business” (a now familiar leitmotif of many conservative political campaigns). Brownson, though, was very clear that his version of the republic would be a theocracy led by the Church of Rome in order to rescue the country from ruin.

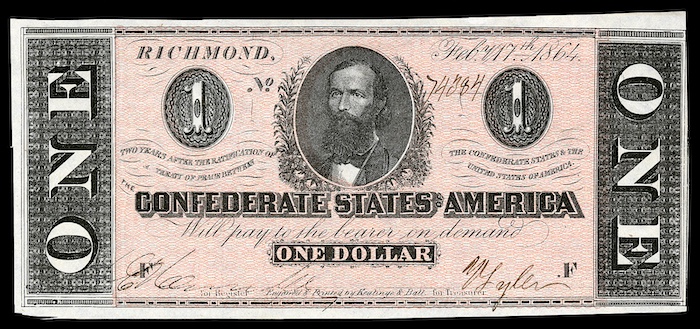

Despite the nullification crisis and other disagreements nudging America towards a civil war, the expression that had emanated from Federalist №10 still rarely popped up in public discourse until pro-slavery congressmen began to thrown it around in 1858 to complain about Kansas becoming a free state, a la Rep. George Taylor (D-NY), or to make Calhoun-y Madison-invoking speeches, from the likes of Senator Clement Claiborne Clay (D-AL), about a republic being the only “stable and conservative” form of government which could keep slavery in the South from being ended by some tyrannical equality-minded democracy.

Eerie utterances to see 160 years on, but we should keep in mind that a few years later Clay became a conspicuous member of the Confederate’s Congress, co-created a network of secret spies for the South, suspected of organizing Lincoln’s assassination, and whose face was printed on their money.

1880s Political Campaigns and an Eccentric Anti-Suffragist

The US Civil War was distracting enough that, for at least a couple of decades, few cared to ponder the specificity of the country’s descriptor. Instead, political creatures of all stripes applied both terms mostly interchangeably. But in 1882, to give a taster of what was to come a half-century later, the Republican Party drafted a textbook of campaign talking points as a response to the 1876 election, in which the Democratic candidate received 184 uncontested electoral votes to the Republican’s 165.

Four states returned 20 votes-worth of disputed electors, which Hayes ® needed in order to win the presidency. The resulting Electoral Commission and the 1877 Compromise essentially ended Reconstruction, leaving Blacks with negligible political support and protections in the South under Jim Crow laws. (The debacle also led to the 1877 Electoral Count Act and why Pence could not reject electors in January of 2021.)

Going forward, as per the Republican manual, campaigns were to emphasize that if enough voters in low-population states are represented by a majority of electors overall, even when vastly outnumbered by the votes in heavily populated states, then the election should be considered legit. Non-Americans looking in could justifiably dub this “tyranny of the minority,” as the campaign textbook pointed out that the six electoral votes of Delaware and Nevada’s 43,824 human votes equaled the same as California’s 154,459. But “American Exceptionalism” also means reveling in lopsided systems as long as one waves the flag the hardest and mendaciously paints “democracy” as the opposite of any constitutional checks and balances, despite contemporary democracies elsewhere having exactly all that enshrined in their own constitutions.

Another aspect of exceptional Americanism is conveniently forgetting recent pasts. The abolitionist establishers of the Republican Party had came up with a very democratic principle for their third plank in their party’s original 1855 platform…

So the Gilded Age kicked off with the rather exclusive usance of “We’re a Republic, Not a Democracy” by a very privileged monied class of eccentric white people.

In her 1885 book, How We are Governed, lifelong anti-suffragist Anna Laurens Dawes leaned right into the conflation of “democracy” with “pure democracy” to accompany this RNAD verbalism. Even as she perfectly described “democracy” as the choosing of representatives in a large nation like the U.S., she also declaimed “democracy” to be unworkable for large nations such as hers.

Dawes spent much of her life railing against allowing women to vote, maintaining that “feminine nature is unsuited to government” and became famous for two controversial publications. Her philosemetic 1886 The Modern Jew: His Present and his Future book does a decent job predicting the creation of Israel. But as most philosemetism tends to go, it was held a heavy air of antisemetism with its othering-focus on Jewish people, who in her view, were not being expected or able to be an meaningful elements of society.

The rich elitess' 1917 The Indian as Citizen was written to support her father's Dawes Act of three decades prior, which forced Native Americans to assimilate into American society to remove any last vestiges their own self-government.

Who would suspect that an affluent socialite, whose father had written legislation to strip away Native Americans’ governance over their own communities and lands, would be against allowing half the country to cast ballots in their country’s polls and be so oppositional to democracy’s most basic tenets? Honestly at this point, we would.

___

(because of some sort of surprise technical issues that we have zero control over, when we came back to edit links and clean up some crappy grammar, we had to delete the first post and then break the first part into two sections in order to update it. So if you are with us, on to part 2 of part 1 of 4) #Democracy #weAreARepublicNotADemocracy #Republic #AmericanHistory #altRight #Libertarian #HeritageFoundation